A Critique of Economic Epistemology

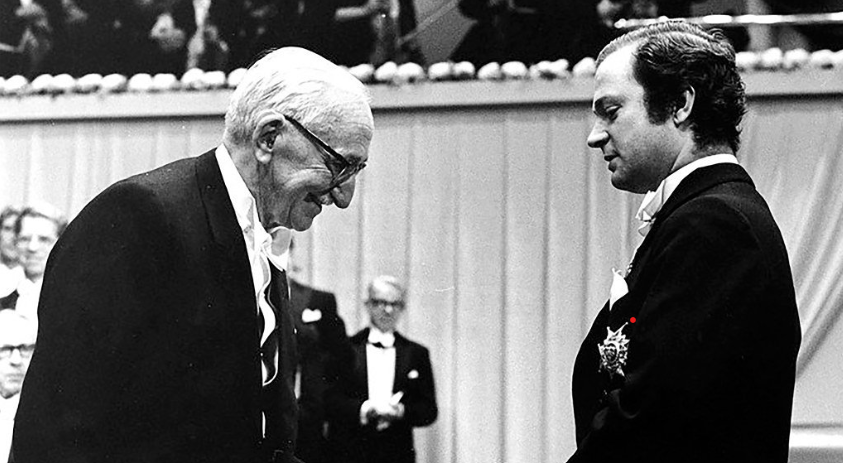

Friedrich Hayek’s 1974 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “The Pretence of Knowledge,” serves as a timeless cautionary tale against the hubris of centralized economic planning. Delivered amidst the economic turmoil of the 1970s – a period marked by stagflation and unemployment, the direct consequences of decades of Keynesian interventionism – Hayek’s lecture dismantled the notion that economics could be treated as a hard science capable of precise prediction and control. He argued that the inherent complexity of economic systems, coupled with the dispersed and often tacit nature of knowledge, rendered comprehensive economic planning not only ineffective but potentially dangerous. Hayek’s central thesis revolved around the limitations of human knowledge, particularly within the intricate web of a modern economy.

Hayek meticulously deconstructed the flawed assumptions underpinning centralized planning. He highlighted the fundamental difference between the study of complex phenomena like economies and the study of simpler, more predictable systems found in the natural sciences. Economists, he argued, often mistakenly applied methods suitable for physics or chemistry to the vastly more intricate realm of human interaction, where individual motivations, preferences, and local knowledge play crucial roles. This “scientistic” approach, as Hayek termed it, led to a dangerous overestimation of economists’ ability to predict and manipulate economic outcomes. The very act of attempting to control a system as intricate as a national economy, with its millions of actors and interwoven relationships, distorted the natural flow of information and incentives that drive market efficiency.

The core of Hayek’s critique lay in his understanding of knowledge as dispersed, subjective, and constantly evolving. No central planner, however brilliant, could ever possess the vast amount of localized and often tacit knowledge held by individuals throughout an economy. This dispersed knowledge, embedded in individual experiences, preferences, and local circumstances, is precisely what fuels the dynamism and efficiency of free markets. The price system, in Hayek’s view, serves as a crucial mechanism for aggregating and transmitting this dispersed information, allowing individuals to coordinate their actions without needing a central authority dictating production and consumption. Interfering with this delicate mechanism through price controls or other interventions inevitably leads to distortions and inefficiencies, as witnessed in the economic struggles of the 1970s.

Hayek contrasted the flawed approach of central planning with the organic, decentralized nature of market economies. Markets, he argued, are far more effective at processing and utilizing dispersed knowledge than any centralized planning authority could ever be. The constant interplay of supply and demand, driven by individual decisions based on local knowledge and preferences, leads to a dynamic equilibrium that efficiently allocates resources and responds to changing circumstances. This process, though seemingly chaotic, is in fact a highly sophisticated system of information processing that far surpasses the capabilities of any central planning bureaucracy. The market’s ability to adapt and evolve stems from its reliance on decentralized decision-making, allowing it to harness the collective wisdom of countless individuals.

The dangers of the “pretence of knowledge” extended beyond mere economic inefficiency. Hayek warned that the belief in the ability to centrally control economic outcomes could easily slide into authoritarianism. As governments increasingly intervene in economic life, they inevitably encroach on individual freedoms and choices. This concentration of power in the hands of a few, coupled with the inherent limitations of their knowledge, creates a fertile ground for unintended consequences and potentially oppressive policies. The very attempt to impose a rational order on a complex system through centralized control, ironically, leads to greater disorder and a loss of individual liberty.

Hayek’s message remains strikingly relevant today, perhaps even more so than in 1974. As governments around the world grapple with economic challenges, the temptation to intervene and control remains strong. Hayek’s insights serve as a potent reminder of the limitations of human knowledge and the dangers of overconfident interventionism. True economic progress, he argued, lies not in centralized control but in fostering the conditions for free markets to flourish, allowing individuals to utilize their dispersed knowledge and make decisions that best serve their own needs and aspirations. This, in turn, creates a dynamic and adaptable economy that benefits society as a whole. Humility in the face of complexity, coupled with a deep respect for the power of decentralized decision-making, is essential for navigating the economic challenges of our time. Hayek’s enduring legacy is his unwavering defense of individual freedom and his insightful critique of the “pretence of knowledge” that all too often leads to misguided and ultimately harmful economic policies.

Share this content:

Post Comment