Antiracist Revisionism: A Perspective on North and South

The history of slavery in the United States is complex and often misrepresented within contemporary debates surrounding antiracism. A prevalent but overly simplistic narrative suggests that the Southern states were uniformly pro-slavery while the Northern states stood firmly against the institution. This perspective seeks to rationalize recent movements aimed at removing Confederate symbols and renaming military bases, but it overlooks essential nuances in the historical context of slavery. Contrary to popular belief, the divisions were not as clear-cut, as many Northern states had historical ties to slavery and engaged in practices that paralleled those seen in the South. As a result, the characterization of a strictly anti-slavery North opposing a pro-slavery South fails to hold up under examination, revealing a broader narrative that requires critical analysis.

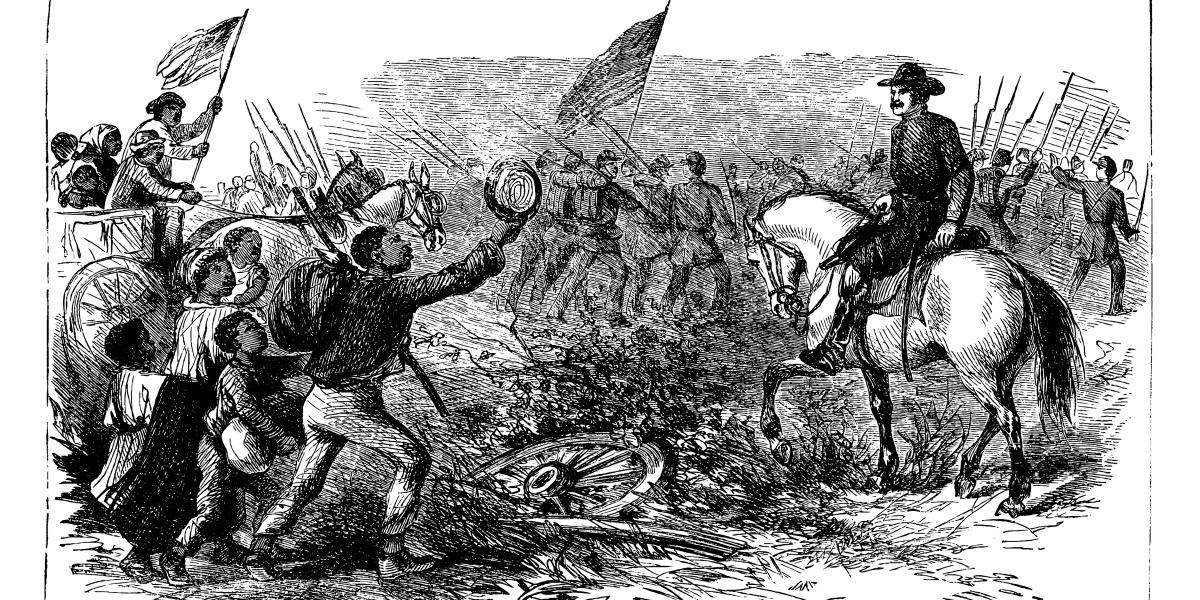

Antiracism often operates within the framework of Critical Theory, aiming to explain and combat the ongoing effects of racism. Key to this discussion is Abraham Lincoln’s motivations during the Civil War, which are frequently portrayed as primarily focused on the abolition of slavery. Such a narrative pressures the interpretation of the Constitution, suggesting that the federal government acted against the South in the war due to a moral opposition to slavery, which the Constitution supposedly did not endorse. However, historians like Michael Zuckert argue that the absence of explicit references to slavery in the Constitution does not mean it endorsed abolition; rather, it accepted the existence of slavery within states that chose to uphold that institution. This misconception about the Constitution has contributed to a skewed understanding of the war’s context and its constitutional implications.

The portrayal of the Civil War as a predominantly moral crusade against slavery is further complicated by the realities of the North’s involvement in the slave trade. While some Northern states, particularly New England, attempted to shift public perception and distance themselves from their historical entanglements with slavery, the reality of their economic and social systems often contradicted this narrative. In many Northern states, including New Jersey, laws that gradually abolished slavery in practice allowed forms of servitude to persist—overlapping lifetimes of bondage with the crumbling institution of slavery. Thus, rather than a unified Northern front against slavery, the reality was fraught with contradictions, complicating claims that the North fought purely for abolitionist motives.

The case of New Jersey exemplifies these contradictions. James Gigantino II highlights how many individuals born into servitude in the state were effectively treated as slaves, despite legal distinctions made in census records. This pattern illustrates a broader trend across the North, where the complexities of labor relations blurred the lines between freedom and slavery. The gradual abolition process does not support the notion of a fervently anti-slavery North ready to wage war for freedom; instead, many Northerners retained structures that permitted bondage well into the Civil War era, resulting in a less than straightforward opposition to the institution. Therefore, the assumptions underlying claims that the North fought solely to end slavery are historically suspect.

Abolitionist movements, while present, were not as widespread or influential as commonly assumed, further undercutting the idea that opposition to slavery was the driving force behind Northern military action. In New Jersey, abolitionists struggled to persuade the public to adopt immediate emancipation policies or provide protections for escaping slaves. Gigantino emphasizes that perspectives on slavery and freedom were understood on a continuum, differing significantly from the binary opposition often presented by contemporary antiracist narratives. This complexity undermines claims regarding the Northern perspective of a moral fight against Southern slavery, indicating that discussions of race and labor were far more nuanced than modern antiracist interpretations suggest.

Ultimately, the simplification of Civil War motives as a dichotomy between freedom and slavery obscures a necessary examination of historical labor practices and ideologies in both the North and the South. The prevailing assumption that the Confederate struggle was only about maintaining slavery while the Union fought solely for liberation fails to survive serious scrutiny. As it stands, the argument for contemporary destruction of Confederate monuments and other symbols of the historical South, informed by this misleading dichotomy, weakens considerably under the weight of historical evidence. Understanding the multi-faceted realities of slavery in America demands a refusal to oversimplify the past as a means of contending with modern debates about race and history. A more comprehensive interpretation recognizes that both regions were implicated in systems of unfree labor, necessitating a balanced perspective that acknowledges historical complexities instead of reinforcing reductive, polarizing narratives.

Share this content:

Post Comment