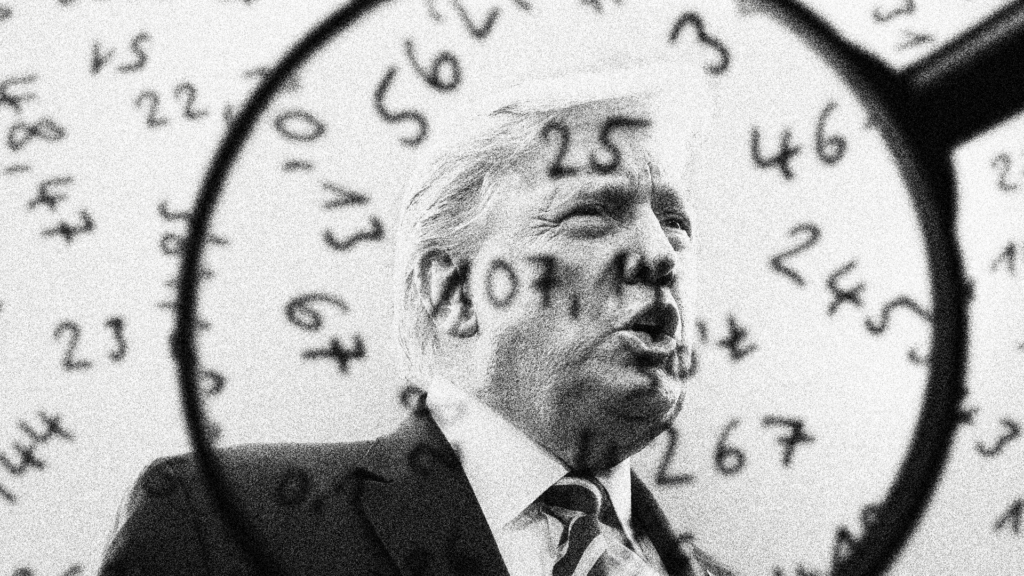

The Numbers Behind Mass Deportation Just Don’t Add Up

President-elect Donald Trump’s campaign slogan “Mass Deportation NOW!” resonated with many, raising questions about the feasibility and implications of such a policy. While Trump’s claims regarding immigrants—including assertions that they contribute to crime and economic decline—are predominantly unsupported by expert analyses, one critical area overlooked in the discussion is the potential ramifications of mass deportation on U.S. government debt. A pre-election report from the conservative Manhattan Institute (MI) suggested that the influx of illegal immigrants could escalate federal debt by $1.1 trillion over their lifetimes, proposing that mass deportations would mitigate this fiscal burden. However, this conclusion sharply contrasts with findings from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which indicated a growing fiscal benefit of nearly $1 trillion from the recently arrived immigrants over the next decade.

To explore the divergence in these analyses, the Cato Institute replicated MI’s study and identified nine methodological flaws within their model that exaggerated the costs of recent arrivals. While MI posited that recent immigrants would lead to a net federal cost of $1.1 trillion, the Cato Institute’s assessment concluded that these individuals would, in fact, contribute a positive net present value of approximately $4.9 trillion to the federal government over their lifetimes. A fundamental problem with MI’s analysis is its assumption that immigrants do not contribute to tax revenues through business activities. This oversights the reality that many immigrants are business owners and workers whose contributions to the economy ultimately lead to tax liabilities, thus contradicting MI’s reliance on misleading census data regarding immigrant education and earning potential.

By misconstruing educational data, MI underestimated the tax contributions of immigrants. For instance, while MI claims only 7% of recent illegal immigrants hold college degrees, recent studies indicate that this number is significantly higher. Many immigrants categorized as “illegal” may not have entered the country illegally but instead arrived under temporary statuses. Further compounding this issue is MI’s assumption that population growth caused by immigration necessitates increased defense spending; however, data illustrates that actual per capita defense spending has declined. Their proposal that Congress would cut defense spending following mass deportation is also unfounded. These inflated cost assumptions were instrumental in MI’s negative projections regarding recent immigrants, but a more accurate framework reveals that these individuals actually pay more in taxes than they receive in government benefits.

Even if one were to concede MI’s premise that recent immigrants would cost $1.1 trillion over their lifetimes, the financial considerations of mass deportation cannot be overlooked. MI estimated the immediate cost of mass deportation at around $500 billion, yet it fails to account for the associated federal debt that such a program would incur, effectively tripling the total estimated taxpayer burden to $1.5 trillion. This staggering figure brings to light the principal irony: even under an assumptions-based assessment that supports the idea of immigrants being a fiscal drain, the economic burden of mass deportation itself vastly outweighs any supposed savings from their removal, creating a scenario where fiscal responsibility is compromised.

The broader implications of mass deportation extend beyond the immediate budgetary costs to encompass lost fiscal benefits from immigrant labor. Though it is crucial to acknowledge that not every immigrant brings a net positive economic impact—particularly those who enter just before retirement or with limited education—the majority can contribute positively if restrictions on welfare access are put in place. By ensuring immigrants are ineligible for welfare benefits, a policy could incentivize those seeking to contribute to the economy, allowing them to potentially transform into positive fiscal entities over their lifetimes.

In general, the advantages of allowing immigrants to naturalize, provided they meet tax contribution requirements, present an appealing solution to the complex integrations of immigration policy and economic viability. The data suggests that the mass deportation policy proposed loses its economic justification when weighed against the actual financial impacts. Promoting responsible immigration while restricting welfare access can lead to an immigrant workforce that is not only self-sufficient but also beneficial to the U.S. economy as a whole. In summary, the comprehensive understanding of immigration impacts in economic terms underscores a need for policies that leverage immigrants’ capabilities, ultimately benefiting American society and mitigating financial burdens rather than exacerbating them through disruptive deportation policies.

Share this content:

Post Comment